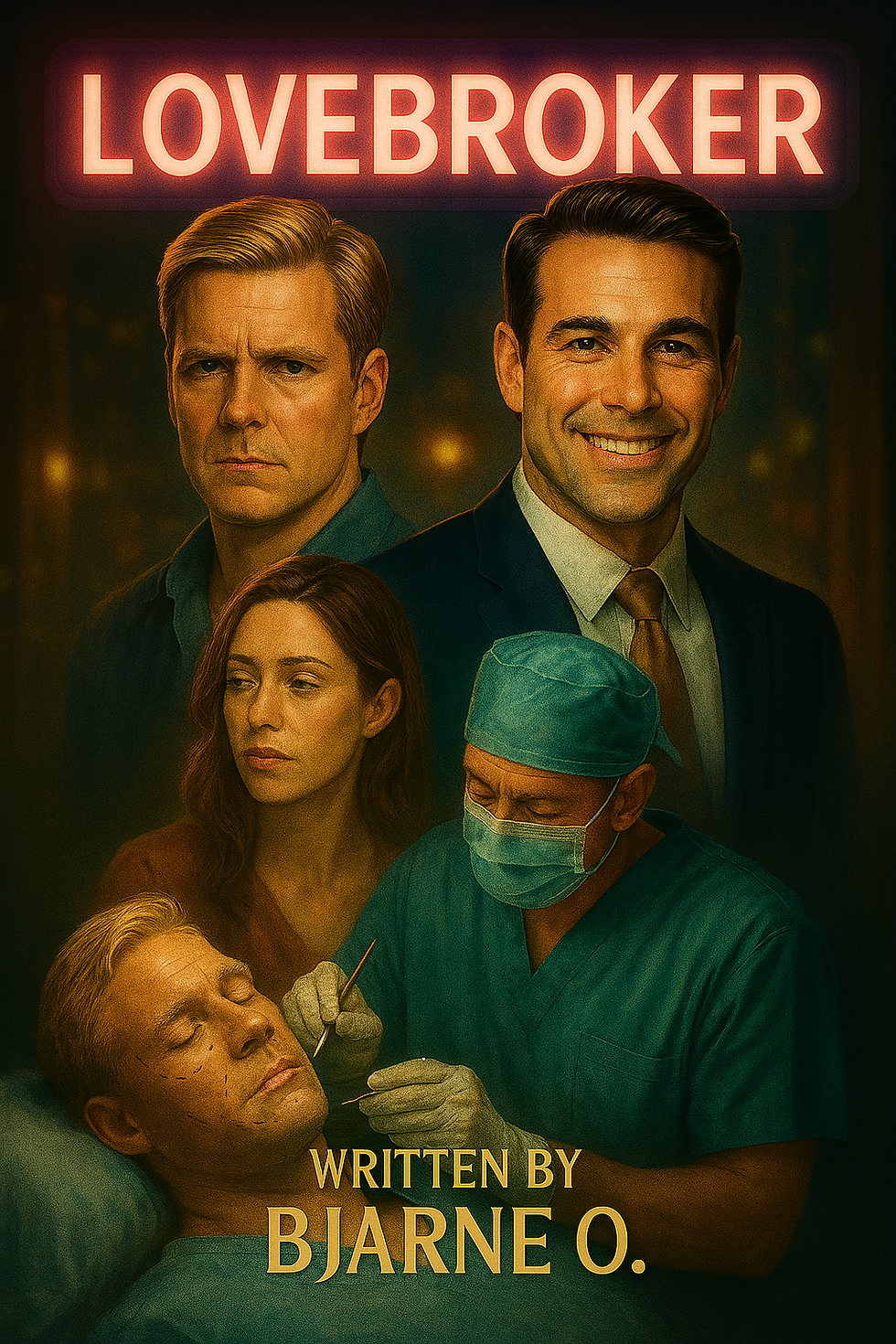

LOVEBROKER

A Screenwriter's Love Letter to Cinema

When established screenwriter Bjarne O. Henriksen adapts his own spec script into a novel, the result is that rarest of creatures: a work that understands both mediums so intimately it transcends their limitations. This darkly comic exploration of modern romance reads like a masterclass in visual storytelling translated to prose—every scene perfectly blocked, every beat calibrated with the precision of someone who's spent decades crafting cinematic moments.

For industry insiders, the novel offers fascinating insights into the adaptation process in reverse. Where most literary adaptations lose something in translation to screen, Henriksen demonstrates how expanding from screenplay to novel can unlock depths that even the best films can't access. The reader can practically see the shot compositions—Arthur's garbage container epiphany reads like a perfectly conceived visual metaphor, while the Target shopping sequences have the satirical bite of the best social realist cinema.

The LoveBroker concept feels tailor-made for the streaming era, arriving at a moment when Hollywood is obsessed with "disruption" narratives and tech industry satire. One can easily imagine this as a limited series for Netflix or HBO Max—the episodic structure is already there, with each of Arthur's escalating romantic gestures functioning as self-contained set pieces building toward the climactic ferry sequence.

What's particularly impressive is how Henriksen uses his insider knowledge of the entertainment industry to craft a broader critique of commodified creativity. The novel's exploration of how authentic emotion gets packaged and sold speaks directly to Hollywood's own struggles with algorithm-driven content creation. LoveBroker's subscription-based romance feels like a logical extension of how streaming services market "content" rather than art.

The character of Sebastian—with his increasingly ridiculous inventions and entrepreneurial delusions—reads like a brilliant satire of Hollywood's obsession with "disruptive" technologies and get-rich-quick schemes. His toilet seat philosophy and silicone sex doll innovations feel like actual pitches one might hear in certain Beverly Hills conference rooms.

Henriksen's cinematic sensibilities serve the prose particularly well in the novel's elaborate set pieces. The IKEA box sequence, the municipal tractor kidnapping, Arthur's surgical transformation into "Robin"—these read like perfectly conceived comedy sequences that could anchor a major studio production. The visual comedy translates beautifully to the page while gaining psychological depth that pure cinema couldn't achieve.

The Casablanca references throughout feel particularly sophisticated coming from someone who understands how film classics get recycled and recontextualized in contemporary storytelling. Henriksen uses Bogart and Bergman's airport farewell not as nostalgic homage but as counterpoint to his characters' commodified romance—classic Hollywood idealism versus modern relationship dysfunction.

For Hollywood critics familiar with Henriksen's filmography, this novel represents both culmination and evolution. The dark humor and structural precision are recognizable, but the medium allows for a more uncompromising vision than commercial cinema typically permits. This feels like the work of someone who's mastered the constraints of studio filmmaking and is now exploring what's possible without them.

The novel's treatment of male desperation and romantic stalking is particularly relevant in post-#MeToo Hollywood. Arthur's behavior would be completely unacceptable in a traditional romantic comedy, yet Henriksen examines it with the kind of psychological complexity that contemporary cinema is still learning to navigate. This isn't love-conquers-all sentimentality but genuine exploration of toxic masculinity and emotional dysfunction.

If there's a criticism, it's that some of the novel's best sequences feel almost too cinematic— readers may find themselves frustrated that they can't actually watch Arthur's garbage container revelation or Sebastian's sex doll demonstration. The prose succeeds so well at evoking visual storytelling that it occasionally makes one wish for the actual film.

Yet this is ultimately the novel's strength: it demonstrates how a master screenwriter can use literary form to explore themes and characters with a depth that even the best films struggle to achieve. In an era when Hollywood is increasingly looking to international creators and stories, Henriksen offers something particularly valuable: a foreign perspective on universal themes, delivered with the kind of structural sophistication that American entertainment often lacks.

This is smart, sophisticated entertainment that could easily translate back to screen while standing alone as significant literary achievement. In a town obsessed with "IP" and franchise potential, Henriksen has created something rarer: original material that feels both immediately adaptable and too good to reduce to mere content.

A remarkable demonstration of how true cinematic literacy can enhance rather than constrain literary ambition.

Awarded the SILVER NYMPH in Monte Carlo for BEST ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY for his debut: Comedy drama "Eddie Holm's Second Life".

“A wry, bittersweet comedy, stuffed with laughs that travel lightheartedly beyond the program’s native Denmark. Includes a refreshingly original series of situations, one-liners, well-bred winks, poignant romance and suspense. A deserved Nymph. "

— VARIETY